5th Studio was established around the idea that there is a bridge – a golden thread – between spatial thinking at the strategic scale, and practical operations on the ground. We are frustrated by the flat economics of much contemporary development, which is all too often driven by spreadsheets rather than by an imaginative vision of a particular place. The market, left to its own devices, prefers to create monocultures and struggles to engage with the risk and spatial complexity which make good cities. We are all familiar with the results in our own cities and towns.

The renewed interest in the garden city was brought into focus by the topic of 2014’s Wolfson Economics Prize, backed by the think-tank Policy Exchange. The prize posed the question: ‘How would you deliver a new Garden City which is visionary, economically viable, and popular?’ Entrants were asked to demonstrate how a new city could be built without ‘a single penny of public money’. Perhaps unsurprisingly, many of the responses to this call imagined a city as an extensive topography of housing, very close to the sort of suburban sprawl countered by Civilia.

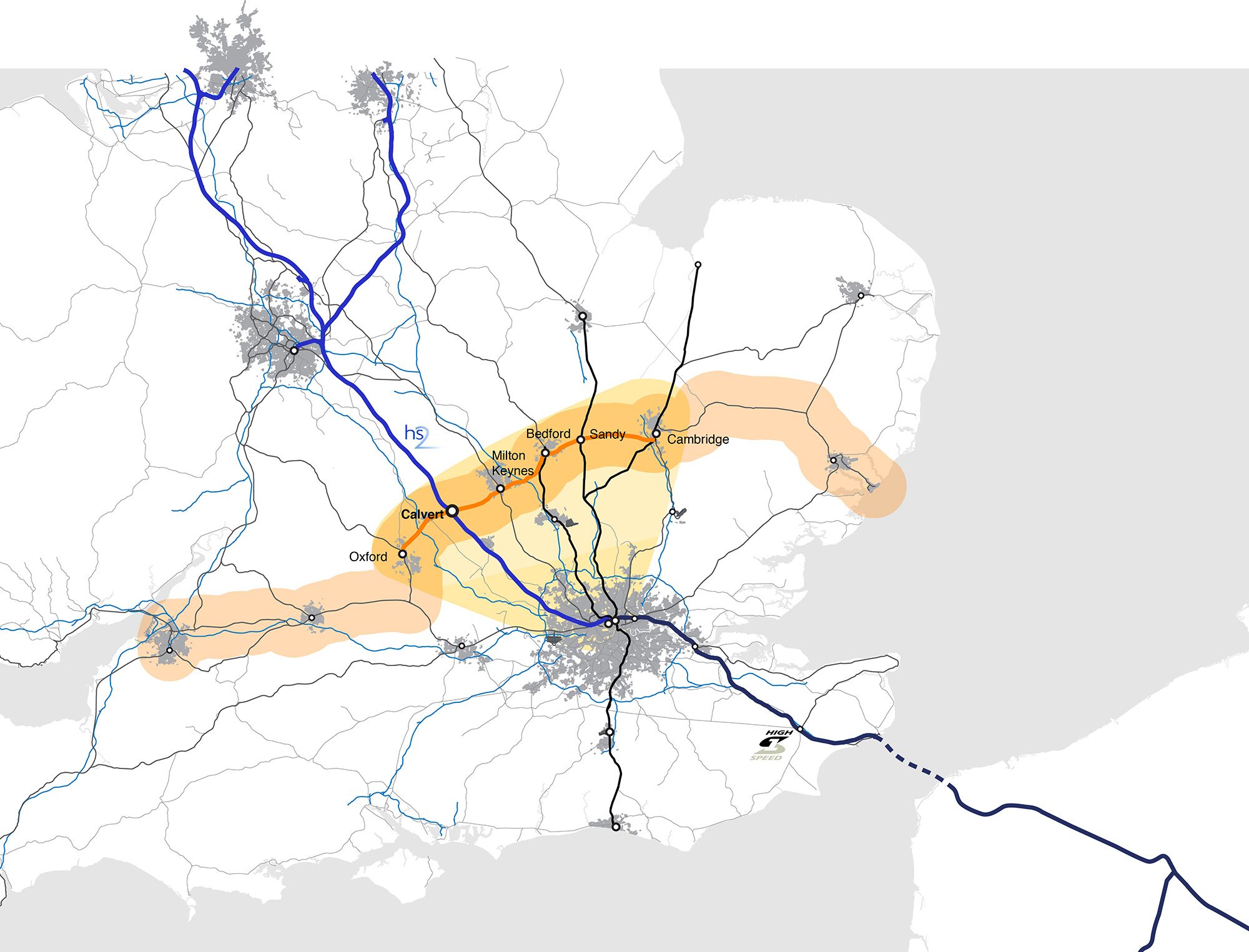

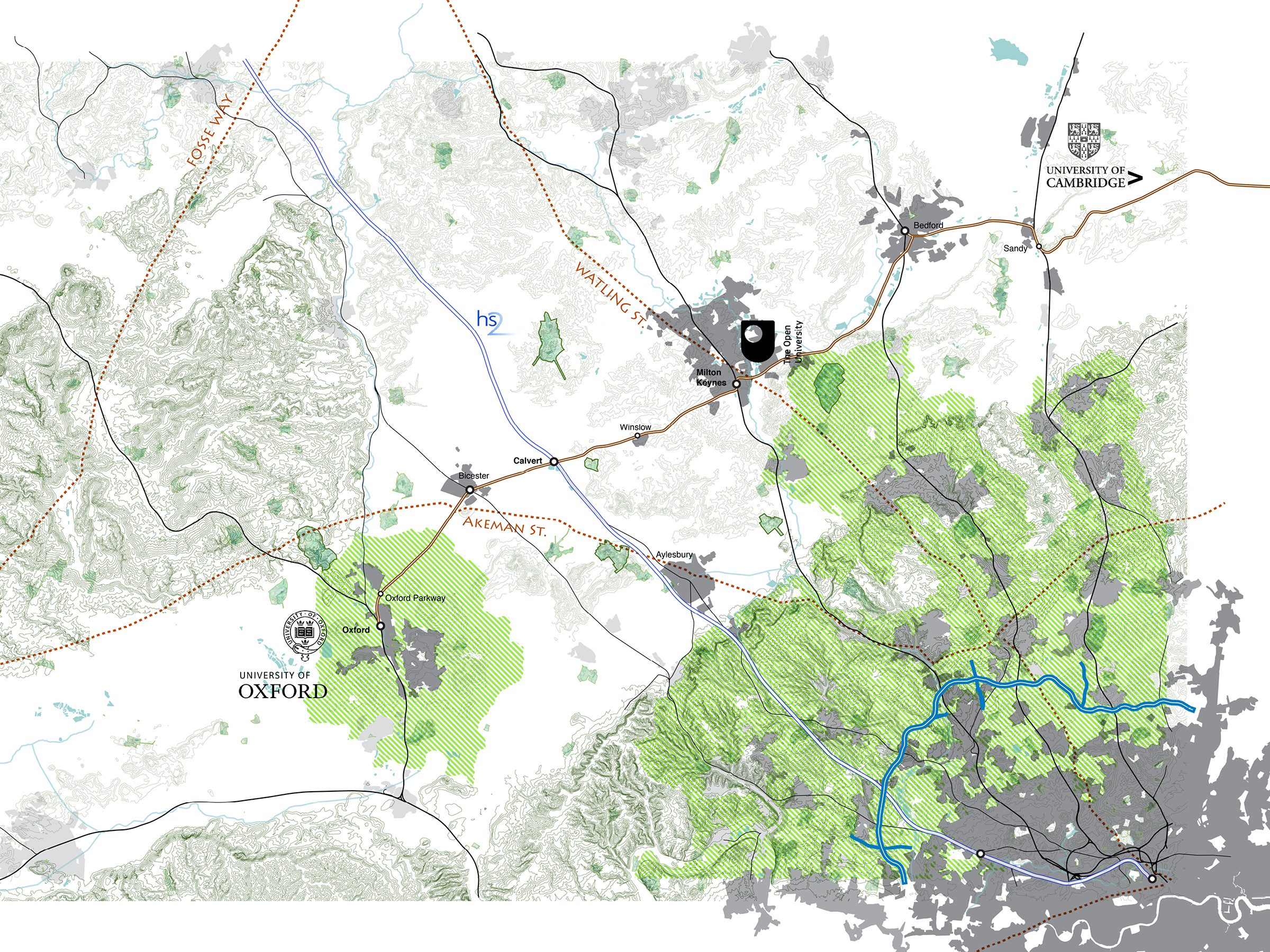

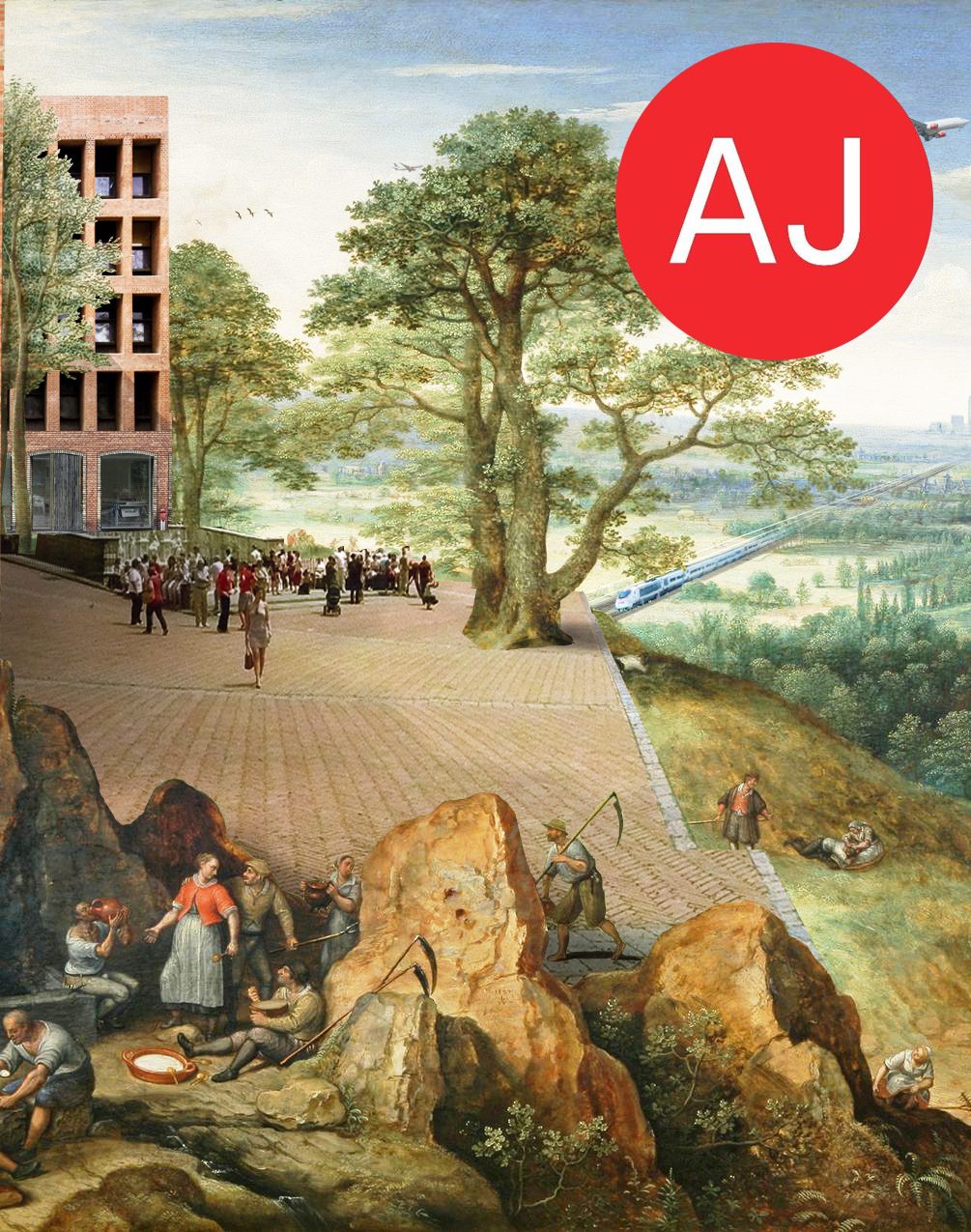

Our entry to the prize, published here, was intended as a critique of the Wolfson proposition. Rather than a garden city, we imagined a city in a garden which, through the combination of public and private agency, creates something truly civic that the market would never deliver on its own. For us, a city embodies an intensity, able to mediate between the individual citizen and the collective. We still expect the state to establish infrastructure, and it is this infrastructure which ultimately endows land with value. We tend to leave huge projects such as High Speed 2 to engineers, but as an exercise in a species of problem-solving, we ask instead: ‘What if the state used that huge investment of money, land and political energy in multiple ways to create delight?’

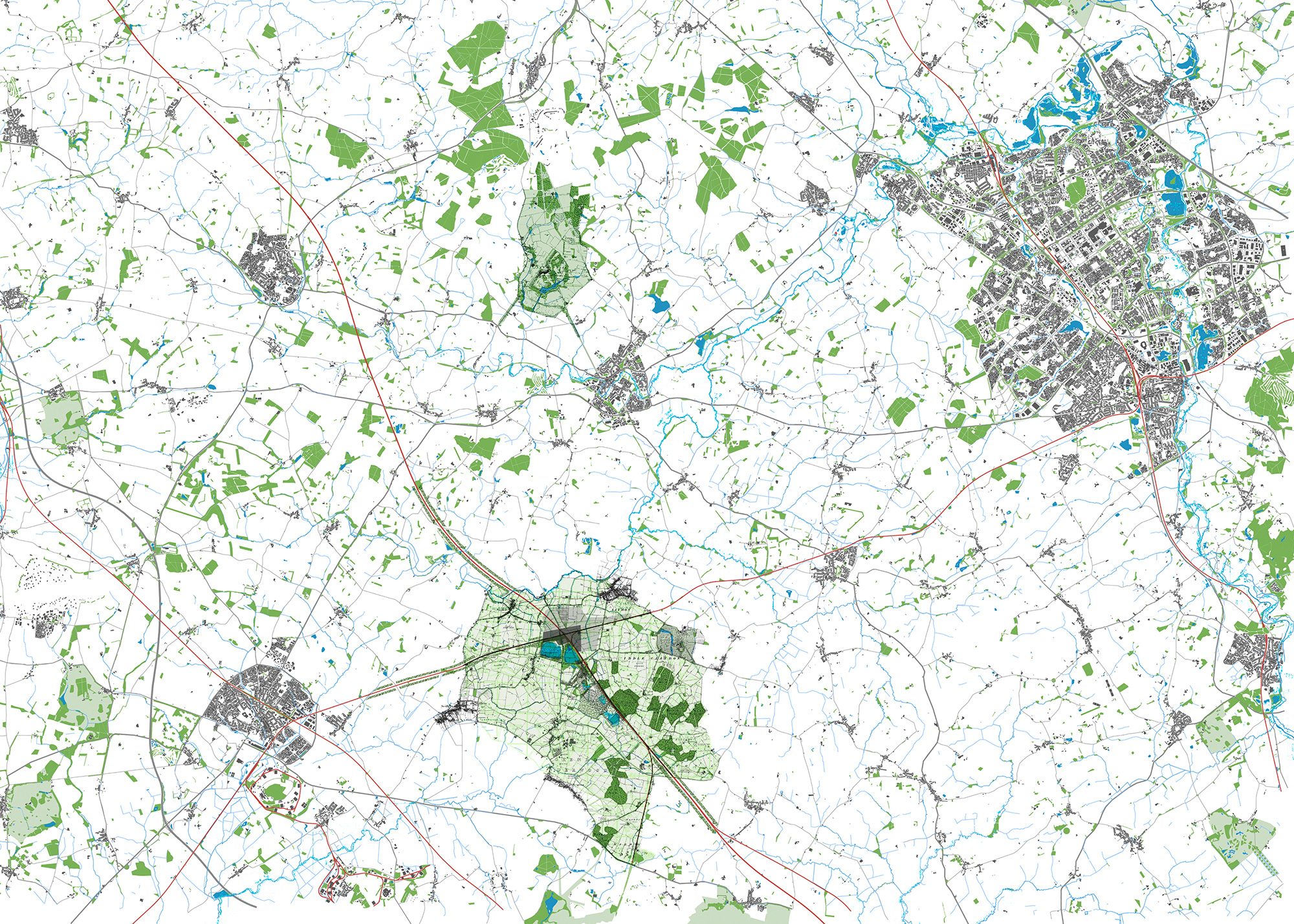

Calvert is a proposition that welds infrastructure, landscape, provisioning, planning and architecture into an intense singularity. Our motive is to fuel a growing debate about the value of spatial planning and the use of land in the public interest.